10. Article on Viable Vision (Gerald Kendall)

Gerald Kendall, TOC International, US

Gerald Kendall, TOC International, US

Gerald Kendall has five published books on TOC reflecting his successes in Project Management, Health Care, Viable Vision and Thinking Processes. He has implemented all elements of TOC with his worldwide clients over the past 22 years.

© Copyright Gerald I. Kendall 2006, 2016 All Rights Reserved

Introduction

“When I do an analysis of a company, I am satisfied only when I clearly see how it is possible to bring the company to have, in less than four years, net profit equal to its current total sales.”

This very ambitious goal, verbalized by Dr. Eli Goldratt [1], is so outside the norm of most company achievements, that many excellent managers laugh when they hear this quote. Sadly, many managers believe that anything even close to this level of improvement is impossible to achieve, especially in a large company.

Yet, in the majority of the hundreds of companies examined over the past three years, this belief was proven wrong—to the extent that many of these companies are now implementing their identified Viable Vision! They are succeeding in the pre-identified steps to turn their top line to bottom line within 4 years.

How is it even possible, let alone likely, that your company can achieve such rapid profit growth? The answer is in two facts:

- Most companies today compete on factors that do NOT provide a decisive competitive edge.

- Most companies today do not have the capabilities to create and sustain a decisive competitive edge.

For example, there are many companies whose salespeople focus on product content (features, quality, customization). Or, within many distributors of commodity products, we find most salespeople focus on aspects such as price, quantity discounts, minimum order quantities, geographic coverage. Some high technology providers see their competitive edge coming from a technical breakthrough.

In all of these companies, these tactics are NOT a decisive competitive edge. They may allow the company to exist and even to flourish for a limited time. However, these points typically do not provide a decisive competitive edge – one that will last for years and sustain a super high rate of growth.

In the Viable Vision approach, a decisive competitive edge implies that your company is meeting a client’s significant need to the extent that no important competitor can. The success is measured in year-after-year of high growth and having more prospects than the company can possibly address, even with internal capacity expanding at a high rate.

Here are a few examples – some of these will be discussed in more detail later in this article:

- Reliable Rapid Response (RRR) – In custom manufacturing industries, it is common to find that many companies are extremely unreliable in due date performance. For example, if you are a customer in an industry dominated by unreliable suppliers, who needs a custom product by a certain date, and you will experience significant damage to your business for every day that the product is late, then reliability is one of your significant needs. Even a supplier performing at 80% on time means that you cannot predict when you will get your product. Any promise that supplier makes is useless because it is unpredictable – 20% of the time, the supplier will miss the due date. How can the customer possibly tell whether or not it will be in the next order? A supplier who has proven 99%+ due date performance, and is willing to provide a written, guaranteed due date with significant penalties for every day late, can easily gain a decisive competitive edge. BUT FIRST, the company must be able to achieve the 99% on time delivery AND their salespeople must know how to sell such an incredible offer.

- Supply Chain / Distribution – It is very common in many supply chains with stocked products, to find that distributors and retailers have most of their available cash tied up in inventory. Even with such massive investment, a strange thing happens. At the same time that they have excesses of many products in some locations, they experience shortages of the very same products in other locations. Any approach that can dramatically increase the availability of these products across the supply chain, while simultaneously reducing the inventory invested in these same products, can be described as providing a decisive competitive edge. However, it must be sustainable, especially when there are a constant stream of new products and when consumers change their minds frequently on how much and when to buy.

- Projects – Some companies undertake major projects either to expand their business, to replace an ailing facility or to meet a government requirement. Examples include implementing new computer systems, building a new plant, opening new retail facilities, constructing buildings, etc. In such major projects, it is common to subcontract large portions of the work to other companies (whom we will call “Project Companies”). In general, the track record of project companies delivering projects on time, on budget and within scope is abysmal. The Standish Group, who repeatedly surveys tens of thousands of projects, quotes statistics of over 70% of projects either late, over budget or out of scope. Project companies can gain a decisive competitive edge by establishing the project management logistics to be able to finish much earlier than your competitors, with a much higher probability of being on time, on budget and within scope. Such logistics begin with an approach called Critical Chain Project Management, but Viable Vision provides other necessary components (such as a structured sales offer) to ensure continued success and increasing margins over the long run.

Viable Vision is unique in its approach, even within companies that are familiar with the Theory of Constraints (TOC) methodology. It is top-down. It is the focus of all top managers for 4 years or until the Viable Vision is achieved, whichever comes first. It begins with a significant, formal buy-in approach, using two forms of buy-in:

- The + buy-in: Showing how the pot of gold can be found

- The minus minus (–) buy-in: Showing major negative situations and how they can be overcome.

Buy-in usually begins with a healthy skepticism from many members of a senior management team. What makes senior management so skeptical? Their disbelief is usually based on the existence of huge obstacles that block a major improvement. It is possible to turn this skepticism around, but only if you can prove beyond a reasonable doubt that you can overcome these obstacles.

This article:

- examines these questions by looking at two different approaches to improving a company—the traditional and the Viable Vision approach.

- spells out the reasons why the traditional approach is popular, but often breeds skepticism and fails to overcome the obstacles.

- explains how the Viable Vision approach works by showing the series of steps necessary to create a Viable Vision that is enthusiastically supported and executed by the entire top management team.

This is the dynamite needed to permanently break down the silos that are cemented in many of today’s management structures.

Two Ways to Manage – Traditional and Leveraged

Most executives currently deal with a very complex environment—one that is far more complex than it was 20 years ago. The Internet, for one thing, has exponentially increased competition and made business life uniquely challenging.

The common practice today, to manage this complexity, is to break down the organization into manageable parts (usually functional areas and departments), and to hold each part accountable for meeting goals within its silo. If you have any doubt about this, just look at your own organization chart and related metrics.

In this mode of management, we see executives spending considerable time to get their silos to cooperate with each other. Individual functional heads interpret what they think is best for their unit and assume it is best for the company as a whole. But often the best we can hope for, in this mode of management, is an attempt to minimize the cross-functional conflicts and damage. Executives become frustrated referees and jugglers, frequently overriding silo metrics in trying to do what makes sense for the organization as a whole.

One typical real-life example is the head of Procurement of a large Bangladesh company who claimed he was saving 70 million Taka (about US$1.3 million) per year by his department’s actions to reduce material costs. His staff spent an arduous year finding reliable and cheaper local suppliers to replace overseas vendors. These same actions were costing US $200,000 per week in lost Throughput, due to manufacturing problems created by substandard materials. The head of manufacturing and the procurement people fought constantly over whether or not the materials were the cause of the problem. The conflicts had become so common that they were just accepted as a fact of life.

We see similar conflicts in most organizations, for example, between Sales and Manufacturing or Sales and Marketing, or between Distributors and Suppliers within a supply chain, between Operations and Delivery personnel—especially in service organizations.

These conflicts are an inherent part of the traditional way of managing complexity. However, there is another way —the Viable Vision approach. This approach also accepts that organizations are a complex beast. To manage the complexity, Viable Vision finds the inherent simplicity (the biggest leverage point) in the midst of the complexity.

This approach assumes that an organization is like a chain. The strength of a chain is determined by its weakest link. Strengthening any link, other than the weakest link, does nothing to strengthen the chain. Therefore, finding the weakest link in the industry (including the Viable Vision company) becomes the leverage point for the organization’s resources. Strengthening it, with a comprehensive, cross-functional strategy and supporting tactics, is the way to ensure exponential growth.

Why the Traditional Approach Fails

With each functional head tasked with and measured on improving their area, they know they must achieve significant change within the quarter and the year to meet their goals. Such change fosters new projects, which each functional head sees as their absolute right to initiate.

Some projects require cross-functional resources. This is where huge conflicts often exist, since these same cross-functional resources (usually in Information Technology, sometimes in engineering or marketing) are in high demand by other functional areas.

The conflicts, however, are not just over resources. For example, if you are the Manufacturing VP, improvement means that you have made your area more efficient. Often, this translates into being able to produce more with the same resources. If you achieve this goal, but Sales is unable to sell your excess capacity, then the pressure is on you to lay off people—something that has many negative ramifications. This can lead to finger-pointing and other ill-feeling in the top management ranks.

There is another major reason why the traditional approach fails. Most companies have a vision, but unfortunately, many visions are not perceived by some key managers or employees as viable. The cross-functional logistics and steps needed to move closer to the vision are not in place. In this situation, each silo feels like it has no choice but to proceed, on its own, to local optima—i.e., to improving within the silo. But without the strongly managed connection (alignment) between silos, many local improvement efforts do not translate into significant bottom line results.

Viable Vision Backbone

Every Viable Vision strategy begins with the same starting assumptions:

- For any company to turn top line into bottom line in four years, their gross profit (Throughput) must grow much faster than their operating expenses. Therefore, no Viable Vision is based on cost cutting as a primary strategy.

- No major improvement effort is sustainable if the senior management team (or other key resources to the effort) must work incredible hours or under extreme stress for years. Experience shows that after a short time, such resources are easily distracted and tend to lose focus.

- There is no need, and indeed it may be harmful, to take high risks. An example of high risks might be capital investment or other actions that endangers the cash flow of the company.

Given these assumptions, the generic Viable Vision strategy has five key elements:

- Build a decisive competitive edge

- Build the capabilities (sales and marketing) to capitalize on a decisive competitive edge

- Ensure there are big enough markets to grow sales at high annual rates, while being selective about the choice of prospects

- A road map that allows the company resources to focus without wasting effort and without exhausting themselves or each other

- A road map that precludes the need for taking risks that are too great

In each Viable Vision, we must identify a client’s significant need that will provide the opportunity to create a lasting, decisive, competitive edge. To be lasting, the competitive edge must never be based on price or cost. It must be in a form that no existing significant competitor can readily copy. In fact, for Viable Vision, we want the competitors to believe that the Viable Vision company is crazy to make such a ridiculous offer to their customers, and that they (the competitor) would certainly never match such an offer. That is one characteristic that makes the competitive edge “decisive”.

In the following examples, you will find detailed descriptions of two such Viable Visions.

Two Examples of Viable Visions

Example 1 – Reliable Rapid Response

In this example, there are certain conditions that must exist in the market in order for a company to gain a decisive competitive edge. These conditions include relatively long lead times (e.g., typically weeks, not hours or a day or two), poor due date performance by most suppliers (e.g., 80% or less – enough that the client cannot count on any delivery date promised), damages to the client as a result of late delivery (e.g., the client cannot manufacture their product, the client cannot unload a ship, the client cannot complete a building), clients do not have ready alternatives (e.g., if the product is highly customized, the client cannot go to a store and buy it), and the price they are paying for the product is small relative to what they are doing or building (e.g., the product is a $2,000 component of a $500,000 airplane).

It is not necessary for all of these conditions to exist in order for the market to be right. As long as clients suffer damage from supplier unreliability, and the product you are selling is a small part of the total value of the client’s end product or entity, there is a good chance that Reliable Rapid Response will work to achieve a Viable Vision.

With the above existing conditions, a company gains a decisive competitive edge when their prospects know that the company is remarkably reliable. Of course, there is an assumption that all other market-driven parameters (price, quality, lead time, range of offerings, etc.) are about the same as the competition.

A company can have a very high level of confidence in a supplier’s due date performance if the company is willing to back up the promise with a hefty penalty (e.g., 10% per day off the price for every day late – 10 days late and the product is free). Still, there are three main components needed to back up this offer:

- The company must build the capability to deliver 99% on time, in spite of variability in the market demand for their products.

- Sales must pursue the right prospects, and get better and better at their close ratios.

- The company’s internal capacity must be continually monitored and expanded before their sales success creates super long lead times.

Once these components are mastered, the company has met all the necessary conditions to begin offering much shorter lead times for a premium. Premiums can be anywhere from 10% to several hundred percent more than list price, depending on the extent of damage the client suffers from unreliability. For example, a precision machine shop in Colorado regularly gets three times their normal price when they deliver a custom part in 1 week instead of 4 weeks. A Canadian kitchen cabinet maker gets 50% more for the same custom kitchen delivered in 2 weeks rather than 6 weeks.

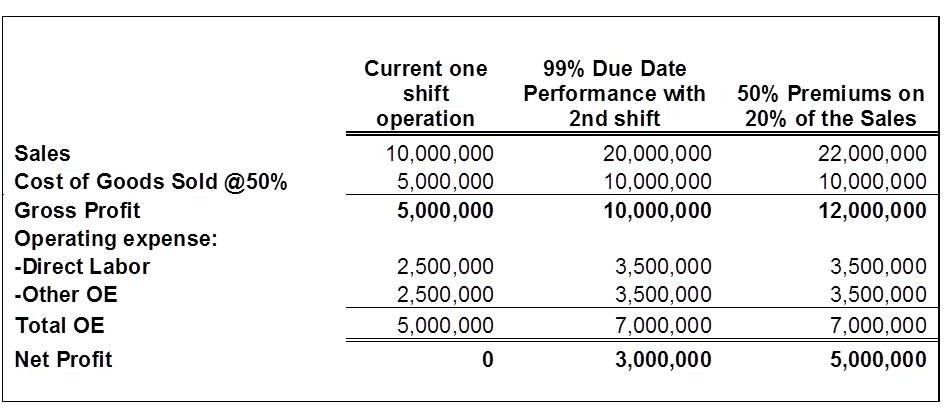

Every extra dollar goes right to the bottom line. Look at what happens to a company’s profits from this approach:

Figure 1

In Figure 1, in the first instance, the company is running one shift per day. From that, they are able to generate $10 million per year in sales. With a 50% cost of raw materials, they are left with half that much as Throughput or Gross Profit. Out of the gross profit, they must pay labor and all other operating expenses, leaving them at a break-even operation – zero profit.Figure 1 – Sales and Profit Impact of a Viable Vision

In the next column, we implement the first stage of a Viable Vision. With the implementation of production logistics, a company’s excess capacity is revealed. Experience has shown that there is often much more excess capacity than the company believes. When you take, as a first step, the rule of thumb of cutting production lead times in half, and releasing that much less to the shop floor, the effect is amazing. The shop floor’s excess work in process contracts significantly, and the excess capacity stands out. Therefore, the company is able to implement a full second shift without having to double either their direct labor or other operating expenses. From experience, the figures shown are generous.

That is why the net profit jumps from zero t o$3 million. But we are not finished. As sales becomes better and better, and the internal team is able to maintain protective capacity and grow resources as needed, we move to the last column, where we implement Viable Vision’s rapid response offer to the market. Before doing this, we must make sure that manufacturing can actually build a product in much shorter lead times, without having to expedite it through the plant. This is especially easy in most plants, which have production lead times far in excess of the actual touch times required to build a product.

In this stage, we are able to get premiums for much shorter lead times, as in the examples cited above. So on 20% of sales, or $4 million, we charge a 50% premium, securing another $2 million in revenues without incurring an additional cent in cost. As a result, our net profit for the same work as we did in the middle column, boosts our profit from $3 million to $5 million.

Once again, building the capabilities to take advantage of the reduced lead times implies significant marketing and sales work. The company must better define their target markets as those prospects who most benefit from their reliability offer. They must establish a pipeline of such prospects. The sales process steps must be defined in detail, and tools provided to the sales force to move quickly through those steps. The pipeline must then be monitored and constantly improved to shorten the sales cycle times and increase the success ratio.

Example 2 – Consumer Goods Distribution

Conditions that typify a consumer goods supply chain include low inventory turns, combined with frequent and numerous stock availability problems. Companies in the supply chain invest most of their available cash in inventory, but still suffer shortages. Suppliers typically make and stock products according to a sales forecast. Forecasts, especially involving end consumer behavior, are notoriously bad.

Distributors and retailers typically use a variation of a min/max inventory system to determine when to reorder stock. Both of these practices (supplying to a forecast and min/max system) contribute to major distortions in replenishment of goods throughout the supply chain. Resulting damage in lost sales, markdowns, obsolescence and lost customers are common.

With these practices in consumer goods markets, it is commonplace to see inventory turns of less than 6 per year, and turns of 2-3 per year are not unusual. TOC logistics changes the mode of replenishment from “push” to “pull”. This is done by linking all parts of the supply chain together to replenish what was actually consumed. Target inventories are adjusted automatically for any changes in consumer demand, or for known seasonality or other known aberrations.

Forecasts are still used at a consolidated level, for major manufacturing planning. However, actual consumption data is affecting the plant finished goods buffers and orders to the shop floor. The entire TOC replenishment system, from manufacturer to end consumer, is built to respond quickly to any changes in consumer demand. This puts the right inventory in the right place at the right time.

Today, many companies try to increase their turns by reducing inventory. The inventory turns can increase, but this can easily mask the bad way the results were achieved. If major markdowns were required to reduce the inventory or worse, major amounts of inventory were written off the ledger books, the turns number could improve, but the company still has poor cash flow and poor availability.

A decisive competitive edge in consumer goods distribution implies that margins are higher than with traditional approaches, turns are much higher, inventory levels are lower and availability across the supply chain has significantly improved.

But there is another common metric used by retailers with consumer goods products – Sales or gross profit per square meter/foot of shelf space. In TOC Consumer Goods Distribution, we call this Throughput per Shelf, or TPS for short. A supplier who has implemented the full replenishment solution can now move to the next stage of increasing their client’s TPS. One approach to do this is to prevent slow-moving products from staying on a given store’s shelf for too long. If the supplier has many more SKUs than they have actual products stocked in a given store, then they can easily substitute one set of SKUs for another.

In retail shops where slow movers are quickly removed and constantly replace with other items, consumers are encouraged to come back to the shop often to see what’s new. A retail chain can also check which products are selling well in comparable other regions or locations, and choose those items to substitute for the slow movers in another location.

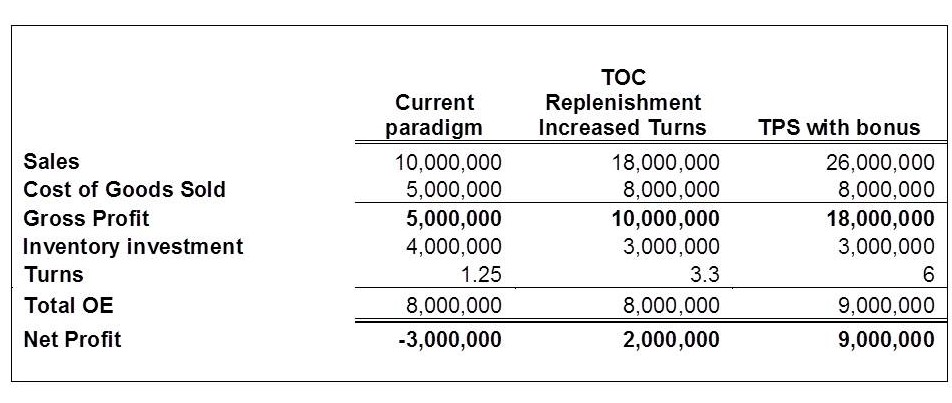

When Viable Vision supplier trains their sales force correctly, they are able to sell business deals to clients, on the basis either of inventory turns or TPS, or first inventory turns moving to TPS as they get to know their clients better. Also, looking at the numbers, the supplier who increases TPS by 25% can demand some of that back in higher margins, and both parties will make a fortune. For an example, see figure 2 below.

Figure 2 – TOC Replenishment and TPS Impact

In Figure 2, the current paradigm has the company generating sales of $10,000,000. With poor availability, the company will suffer from markdowns and obsolescence. Even though they have very lucrative average margins from suppliers (70% plus from overseas), they average 50% because of frequent markdowns. After paying all expenses, they are losing $3 million per year.

In the next column, we implement TOC replenishment solution. The company’s inventory goes down, availability goes up, and therefore sales rise dramatically. There are still some slow movers that the company is not addressing, so while margins improve from the previous scenario, they are still not achieving their full potential. However, turns more than double and now the company has a profit of $2 million.

But we are not finished. Viable Vision takes us to the next level using Throughput Per Shelf (TPS). In this paradigm, we are quickly exchanging slow movers. Sales improve dramatically. Inventory stays the same. We changed transportation logistics and so operating expenses increased. Yet we are left with almost double inventory turns again, and 4.5 times the net profit.

The consumer goods Viable Vision requires extensive sales training and practice. Salespeople must learn which prospects are suitable, and how to ask the right questions to find out. They must be able to do something totally foreign in retail – ask for higher margin for the same product, when the customer is selling more of the supplier’s goods.

Why would a retail customer be willing to pay a supplier more per unit, when they are selling more of the same product? If a retailer’s gross profit per square foot of shelf space doubles per time period, a 5% increase in price, even when they cannot pass that increase on to the consumer, still leaves them with a fortune. It still is much better than any competitive offering without TPS capability. However, it still must be professionally presented by a well trained business deal sales force.

These two examples provide a brief overview and a very small percentage of the current Viable Vision knowledge. Viable Vision implementations have been improved and simplified extensively over the past several years, to achieve results faster and faster with less strain on resources. It is a rapidly evolving, immense body of knowledge relative to how to accomplish major improvement in any size organization. The steps which are generally followed to identify and implement a Viable Vision are described next.

Five Steps to Viable Vision

Five steps are absolutely essential to identifying a Viable Vision and executing correctly. If any one step is missed or executed out of sequence, then the entire effort will be in jeopardy.

Step 1—Collect the data to identify the organization’s leverage point, and the Viable Vision needed to exploit it.

When the Viable Vision process first started, it was common to examine the flow of products and services through a supply chain, of which your company is one piece. A person analyzing the data would look for where is the flow blocked? What is the source of the blockage? How common is this in the industry? What damage is done to the customer, when this blockage occurs?

For example, if there is lots of inventory in the supply chain right through to the end consumer of the product, but there are still many items out of stock in any given location, then the leverage point is clearly with the TOC replenishment solution. The Viable Vision process will use the return on inventory to create a decisive competitive edge.

Some company salespeople bring many prospects to their door and then waste them—they don’t close the deal. Why not? In a Viable Vision, it would not be unusual to see close rates approaching greater than 50%.

In other cases, the company is tapped out of prospects in the markets they serve. They may have a high market share or they may not have achieved a competitive edge, even with a superior product. To reach a Viable Vision, that company may need to explore new markets, or create their own unique “Mafia Offer” – an offer that is too good to refuse for existing or new markets.

However, if creating such an offer requires new products to be developed, the company could suffer for a long period of time before tangible improvements are reached. A Viable Vision must do better than simply relying on new product development.

While over 70% of all companies are currently constrained by not having enough customers to buy their products, there are other possibilities. For example, a company may not be able to produce enough to meet the market demand. This may be a production logistics problem or a project management problem. Sometimes, even when the constraint is in the market, the correct answer to address the problem lies in changing manufacturing logistics to reduce lead time, improve reliability or for other reasons.

The constraint might be in the distribution channel, with suppliers or in engineering or even in sales. Regardless of where it is, the first step is to correctly identify the organization’s biggest leverage point.

Step 2—Gain the buy-in of the CEO to the Viable Vision

Viable Vision is a top down approach. What the CEO understands and supports gets done.

This critical dogma is not just a Viable Vision concept. It has been proven through research and empirical evidence and stated in the most popular management books—Good to Great, Execution, Six Sigma, Lean Thinking and many more.

In the Viable Vision process, one successful approach, that lends itself to further buy in from the top management team, is to draft a “straw man” Strategy and Tactics to achieve the Viable Vision. The draft Strategy and Tactics details, for each functional area, the required elements to achieve the Viable Vision. Usually, the CEO goes through a few iterations of the Strategy and Tactics document until he/she understands, agrees and is fully committed to supporting it. It makes no sense to move forward with the process unless the CEO fully understands how the Viable Vision will be accomplished, what the necessary strategy and tactics are, the assumptions behind the financial achievements and the strong desire to achieve the results. It is rare that a CEO has turned down such an opportunity. However, if a CEO has a different vision or is not prepared to make the Viable Vision Project THE MAIN PROJECT of the company for four years, the process will stop at this point.

It is important to note that even though the CEO has taken over ownership of the S&T at this point, his / her team has not. Therefore, it is a straw man S&T until the entire management team has scrutinized it, bought in and is committed to it.

Step 3—Gain the buy-in of the entire top management team

CEO buy-in is necessary, but not sufficient, to ensure the successful paradigm shifts for a Viable Vision. Therefore, the next step is to help the top management team understand why, for so long, their company was blocked from exponential growth.

Before all of the top managers can accept a Viable Vision solution, they must see a road map that makes sense. They must understand the systemic changes that they will take responsibility for implementing in manufacturing logistics, supply chain replenishment, project management, marketing and sales.

In the Viable Vision process, this step is accomplished in a one-day joint working session with the top management team, led by a Viable Vision expert. 100% top management team concurrence is necessary to proceed.

Step 4—Strategic Planning Kick-Off / Overview Education

Before building a strategy, all of top management must see the company through the same eyes. The current process follows a strategy and tactics road map, which has the following components to several levels of detail (most of the current templates are taken to four levels of detail):

- A Strategy – What we want to accomplish

- Existing assumptions that explain why this specific strategy was chosen

- The tactic(s) needed to accomplish the strategy

- Assumptions which explain conditions that exist which the tactic(s) must overcome or existing conditions which allow the tactics to work so well in achieving the strategy.

For example, when working to identify target markets in consumer goods companies, we know how easily salespeople can get turned off by pursuing the wrong prospects. It is so easy for them to jump to the conclusion that this Viable Vision stuff just does not work. We also don’t want to waste their time with useless prospects. These assumptions explain why our strategy must be to have salespeople know which prospects are the best ones for the Inventory Turns offer.

To get to a valid tactic, we must know some details about our target market. For example, one assumption we will use is that the greater the number of SKUs, the more slow movers you tend to find, and therefore the more powerful the offer. Now it’s obvious that one of the characteristics we must look for in a target market is the right range of number of SKUs.

The process takes each block of the strategy and tactic structure and presents it to the company team. As the strategy and tactics are outlined in more and more detail, there will be a point where some of the detailed knowledge of the application (manufacturing, distribution, marketing, sales, project management) is conveyed to the group. With this knowledge, the group is able to define any reservations they may have about the solution (specific element of strategy or tactic).

Every reservation is gone over rigorously, either to prove that it is already taken care of in the strategy and tactic structure or it is noted as a point to consider during implementation. At the end of the process, which is best kept to no more than 2 days, the project plan is put together by assigning team members to each relevant piece of the structure at the most detailed level.

Step 5—Implementation

After a successful kick-off, Viable Vision becomes the company’s only major initiative. Every top manager is directly involved. Viable Visions use the TOC Project Management approach called Critical Chain. The project is actually planned to be achieved in 2.5 years. The remainder is a buffer. When the Viable Vision process is working correctly, significant results should be observable in weeks or at most, a few months.

Summary

In America today, executives are given about 20 months to prove themselves by delivering increased profits – bottom line results. In 57% of the companies surveyed in a three year period, CEOs failed to do so and were fired. What about in your country? It is just my humble opinion, but from my worldwide experiences, I see all countries having great challenges in technology, productivity and quality.

Many countries around the world are coming out of a long period where productivity was measured much more by internal country standards than by international standards. Yet to be successful and to enjoy real growth in personal wealth, you must be able to compete in business on the world playing field.

China, India, Vietnam, Korea and other emerging players are hot on everyone’s heels, not just in the cost of products, but in quality and design innovation as well. The Chinese have accomplished in 20 years what took the Americans and Japanese over 100 years to achieve. Malaysia and India are paying attention, and their economies are poised to boom over the next decade. The pressure is on your executives and managers to perform miracles.

Over the past three decades, most countries have had major improvements in schooling, especially in business. Business people have proven their ability to work hard and compete in the international arena. But the pressure of the advances in foreign competition took its toll. Today, hard work and low wages are simply not enough to win. Amazingly, the 9 countries I have worked in over the past 22 years [2] all take a similar approach, and bring comparable management skills to their work. What now is the key to drive a company to success?

My answer is that the key to success is the same one that is working equally well worldwide. Viable Vision is the logical extension of Dr. Edwards Deming’s work of the last century. Viable Vision brings the management team to identify and exploit its biggest leverage point for improvement. It focuses the now precious human resources on those key constraints of the business. It aligns the management team not just to work in harmony, but to work in the correct sequence on the right initiatives to achieve huge success. It overcomes one of the biggest constraints to any organization’s growth – the market – by identifying new and unique ways to bring major value your existing and your competitor’s customers.

Any country’s business management has a great, but limited history of achieving results. At the same time, every country has major obstacles to overcome. Viable Vision is, I believe, the missing ingredient to drive new, high growth and secure the future.

[1] Goldratt is the founder of the Theory of Constraints (TOC), author of the multi-million bestselling book, The Goal and several others, including Critical Chain, Necessary But Not Sufficient, It’s Not Luck, The Haystack Syndrome and The Theory of Constraints.

[2] Malaysia, Bangladesh, Australia, Switzerland, Italy, Canada, Poland, Germany and United States