3. Whatever We Do or Say Is for a Purpose: The Role of Communications in Change Management. Part 1 (Jelena Fedurko)

Jelena Fedurko

Jelena Fedurko

Jelena Fedurko has been transferring and developing TOC knowledge, supporting TOC implementations in operations, distribution, project management, marketing and sales and people management since 1999. She has worked in more than 15 countries.

Jelena is a Co-Founder and Co-President of TOC Practitioners Alliance TOCPA, International Director of TOC Strategic Solutions and a TOC Expert in tocExpert. Jelena is an author of several books on TOC Thinking Processes and TOC Basics, as well as many articles and publications.

jelenafedurko.gs@gmail.com www.tocexpert.com

Part 1

The meaning of the communication is the response that you get.

Joseph O’Connor and John Seymour

ABSTRACT

The biggest challenge in implementing change is making it happen. Without the collaboration of people whose lives are going to be affected by the change, it is hardly possible. Ability to recognize what change means for people, and their reaction towards the proposed initiative, is crucial for leaders. They must understand how to influence the attitude of their people, and how to build agreement and enthusiasm towards achieving the required improvements.

Management often takes it for granted that a good solution, especially one that has proven to be successful in other companies or other environments, will work. However, even a very good solution is only a part of the success. The other and very meaningful part is the ability to excite people to take the solution on board and put effort into making it happen.

In determining success or failure of any initiative, especially a major one, the key factors will often be the leaders’ ability to persuade and excite, to create trust and lead, often by personal example. This requires strength, passion and vision. No less, it requires good communication skills, knowledge of concepts and techniques of motivation, and understanding patterns of thinking that are reflected in peoples’ responses and behavior.

The aim of this article is to look at the type of changes that TOC brings into organizations through the prism of understanding and interpreting peoples’ behavior. The purpose is to build change-related messages so as to adjust them to the specific communication patterns of the people we need to win and involve in the change.

As the basis for communication patterns, this article uses the Language and Behaviour (LAB) Profile (1986) by Rodger Bailey[1], and practical recommendations of how to apply the LAB Profile for building a persuasive message as presented by Shelle Rose Charvet (1997)[2]. I learned the approach from Shelle Charvet in a series of training sessions in 1997-1998, and I have been using it since then. I find the techniques very helpful and enabling, easeing the process of communication through matching the language of responses to the communication patterns of counter partners.

Two types of change

This part of the article looks into the differences between the desired change and one imposed from the outside, as well as the differences between people’s attitudes and behaviour relative to the type of change they are facing. What I am presenting is, to a great extent, a reflection of my personal experience and observations. I have seen how people handle major change and themselves as the change is happening around them.

I come from a very small country of 1.4 million people that went through a drastic change from being a part of the former Soviet Union to eventually becoming a member of the European Union. (Just recently, it also moved monetarily over to Euro). I believe I can understand what a major change means, and what it involves.

From the point of view of people’s attitudes and behaviour, we can distinguish between two types of change:

- the change that people seek themselves, or “dream about”, or work towards getting, and

- the change that is imposed from outside and people have to do something about it.

The key difference is in the perception and expectation of a person regarding the outcome that the change will bring for them personally – benefits or negative outcomes.

When we look at the first type – the change that people seek themselves, there are two main states in which people find themselves:

- “I do not want any longer what I have now”, and

- “I want THAT (something specific).”

When it is the “I do not want any longer” state, very often a person has no clear understanding of what it is that s/he wants. Usually, it is just a realization of being dissatisfied with the current state of things, and a wish to change it. However, the person does not know, or is indecisive of, what to change to. In other words, a person seeks change, but has no clear vision of the direction in which to go. There is no clear and well-formed vision of the desired change’s outcome and no understanding of how to achieve it.

It seems easier for a person in the “I want THAT” state, as there is a vision or understanding of what it is a person wants. There are people who intuitively know, or have been trained in how to determine, the desired outcome, to set the goals to achieve it, and have the mechanism to assess whether they are moving in the right direction. If they are not, they know what corrective actions they should take.

However, we should not forget that the ‘THAT’ is only perception. If the hopes are too high and the reality turns out to be different, it may result in disappointment, frustration and the bitterness of being disillusioned.

So, even handling the change that people want themselves is not that straightforward.

Dealing with the change that is imposed from outside is truly challenging.

People are naturally cautious about the change that was not initiated or desired by them – about what it will bring. They need time to think about it and decide whether they like it or not. Often the immediate concern would be that the change planned by someone else will bring disturbance to the person’s everyday life – routine, work, daily activities – and will result in additional load. As a rule this concern is justified because any change demands an effort.

With the imposed change, there are different change-related conditions:

a. A person has no influence over the decision to make the change, and no choice of not accepting it without physically moving themselves out of the changed environment. However, this would often be impossible or too big a move to undertake only because they dislike the situation. In this case, people learn to behave in line with the change.

A simple example of that would be what I was observing at the beginning of year 2011 when my country was going over from the national currency to Euro. Regardless of whether an individual was enthusiastic or unhappy about it, or how much effort had to be put into learning the new currency, understanding the new prices, etc, people had to accept the change and learn how to handle it in order to keep operating in the society.

b. People can ignore the change – both at the stage when the system is just considering the change, as well as after the decision about the change implementation is made. When saying “people can ignore”, I mean that the system does not have the control mechanism to ensure the change implementation, or is not employing it. If this is the case, the sequence of events and efforts that the system’s owners or managers pursue does not matter, (whether they first promote the change and then make the official decision about its implementation, or the other way around). Any change requires an effort. If people do not want it, and can refrain from making the effort that they see as imposed on them, then this is what is most likely going to happen. What we often see then is a few enthusiasts personally excited about the change and pushing for it, and the majority who are trying to avoid the disturbance and extra effort that they associate with the imposed change.

If there is a lack of proper communication about the details of the change on the side of management, it strengthens in people the feeling of not being in control, and reinforces their concerns. The change becomes even more unwelcome.

Management communication deficiency, however, is not caused by disregarding those who will implement the change and live it. After all, managers bring change with the view of improving their systems. One way or another, the change will translate into benefits for those who operate in the system. At least, this is an expectation.

The reasons for difficulties with change communication are various. Often leaders want just a “big picture”, what they believe the organization will get as the result of change implementation. If the solution is credible and proven, or if it fits their vision and belief in the potential of their system, they do not feel they need the persuasion of the details, the exact content of the change, and the HOW. They may overlook the importance of these to people in the system. Some leaders are by nature quick, proactive and entrepreneurial. They see that as their strength and have the experience of getting things done through the approach of “Just do it, we will sort it out when we get there”. Some do not feel there is a need to tell their people all the details, and certainly not the risks, to avoid creating a feeling of complexity and discouragement.

Many times they simply do not know how to communicate the planned change so as to get the support and enthusiasm of the troops.

Throughout this article I will be sharing with you what knowledge, concepts and techniques regarding communication and motivation I find to be useful in the process of change management.

Our actions and words are for a purpose

I believe the cornerstone of successful communication is the ability to realize that whatever we do or say is for a purpose. In other words, through communicating or acting we are trying to achieve something, whether we are conscious of it or not.

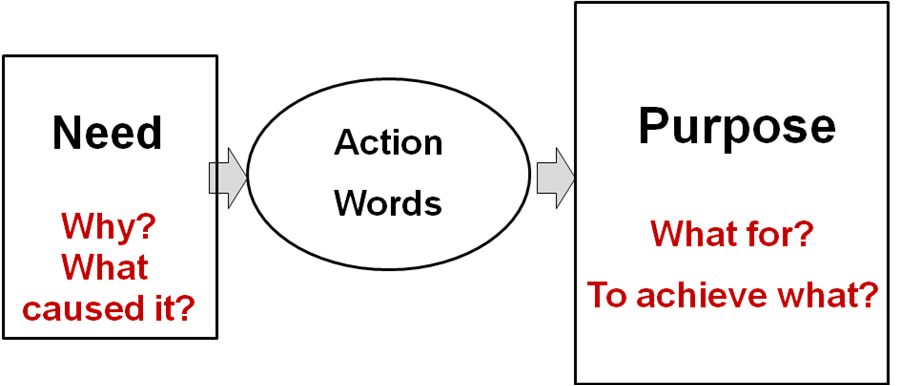

Quite often people confuse the purpose and the need. Don’t we undertake an action with the purpose of satisfying a need? It looks like a circle. For communication, however, it is important to understand the difference. The need is the cause. Actions/words are the effect. We expect them to bring about the desired outcome which is a lot more concrete and tangible than the generic need it manifests. Words and actions are nothing more than the means to get what we want.

Figure 1: The interrelation between the Need, the Action/Words and the Purpose

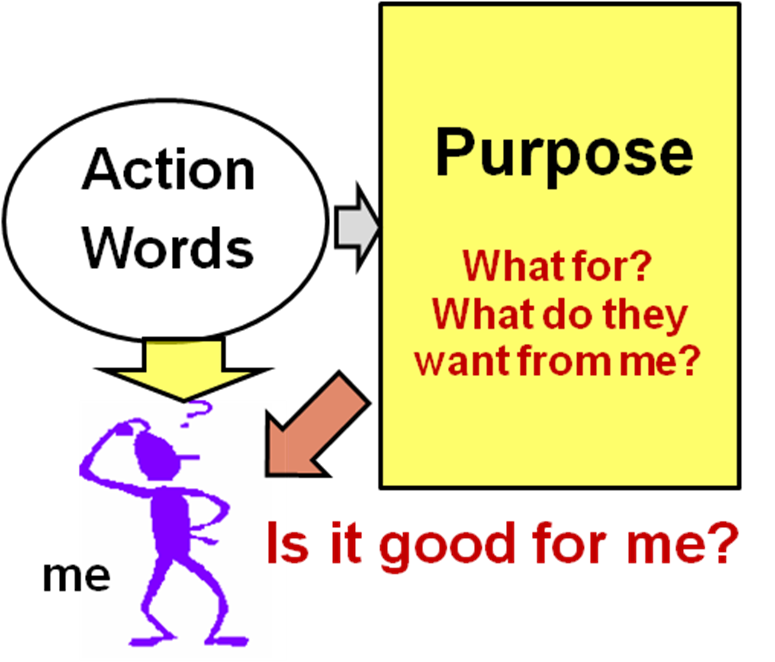

When actions/words are directed towards us, we want to understand what the person is trying to make us do? In other words, consciously or subconsciously, we are trying to understand the purpose of what was said or done to us.

Figure 2: Checking whether what was said or done to us is good for us

It is surprising how often people have no conscious understanding about the purpose of what they themselves have said or done. Did it ever happen to you that you asked someone “Why did you do/say that?” and got a sincere response “I do not know”?

Related to that, there are some important questions to think about:

- Do we always realize that, because we live in a society, whatever we say or do is actually directed to other people as a request/instruction for their action?

- Do we always check that the other party will perceive our request/instruction as good and beneficial for them?

- Do we ourselves check that our request/instruction will be good and beneficial for them?

- Do we do our homework to help them see that it will be good and beneficial?

These questions are important because if people do not see our request/instruction as good and beneficial for them, we have a very little chance of getting what we want.

Communication and motivation

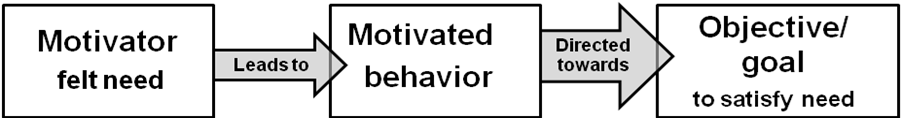

A generic and well accepted model of the motivation process looks like this:

Figure 3: The generic model of the motivation process

When we consider implementing a change – we want to understand all three elements of the process of motivation:

- What are the needs that motivate people to take actions in different contexts? Especially, what are these needs in the context of the proposed change?

- What is the resulting behaviour triggered by the need?

- Achieving what goal/objective/purpose will satisfy their need?

Let’s return to the question that we asked earlier: Do we always realize that, because we live in a society, whatever we say is actually directed to other people as a request/instruction for their action?

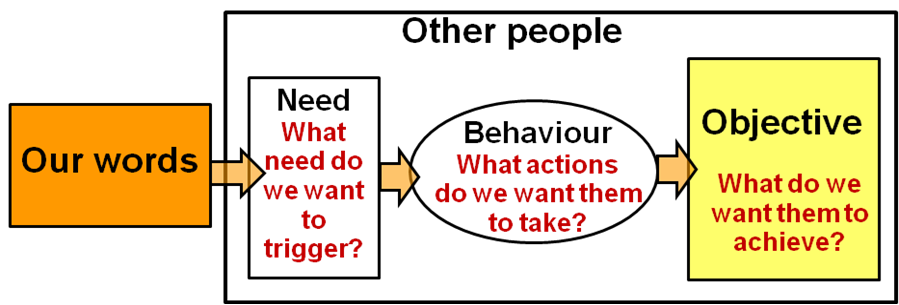

In change implementation, when we communicate with the people who will become a part of the change and will contribute their efforts to making it happen, we want our words to be a motivator for their behaviour – to trigger their need for action to achieve the desired objective.

Figure 4: Our words as a motivator for other people’s behaviour

I would like to quote here J. O’Conner and J. Seymour:

‘Communication is a loop, what you do influences the other person, and what they do influences you; it cannot be otherwise. You can take responsibility for your part of the loop. You already influence others, the only choice is whether to be conscious or unconscious of the effects you create.’[3]

I find the statement about each person’s responsibility for their part of the communication loop very meaningful. Responsibility requires a measured and thoughtful approach, understanding of consequences, accountability and integrity. Whatever we do or say should be congruent with our values and should not be at the cost of other people. This fully corresponds to the third basic assumption of TOC that establishes Respect as a principle and the way of handling people, and states that there is no resistance to improvement. If people do not embrace change, it means we have not brought them to see the win for themselves.

The outcome of the communication is the responsibility of the party sending the message. To ensure that the message will go through in the best possible way, the sending party has to be aware of different thinking and behavioral patterns that people produce in the communication process.

With the purpose of better understanding thinking patterns that people demonstrate in the course of communication, this article will look at three of the six Motivation Traits of Bailey’s LAB Profile – Direction, Source, and Reason. The whole LAB Profile concept is comprised of six Motivation Traits and eight Working Traits[4].

Toward versus Away from

The LAB Profile states that a person is triggered into action by an urge to gain a desirable outcome or to avoid an anticipated problem. Based on that, it suggests two motivation directions: Toward and Away From.

From the point of view of the motivation process, it makes no difference whether the objective is perceived as gaining a desirable outcome or avoiding an anticipated problem. It is the motivation of the behaviour that makes the difference: gaining versus avoiding.

Bailey suggests that people with different motivation directions will have different patterns of sentence structure and lexical means that they use in the context of discussing an outcome that they want, or are supposed, to achieve. I believe most of us can substantiate from personal experience.

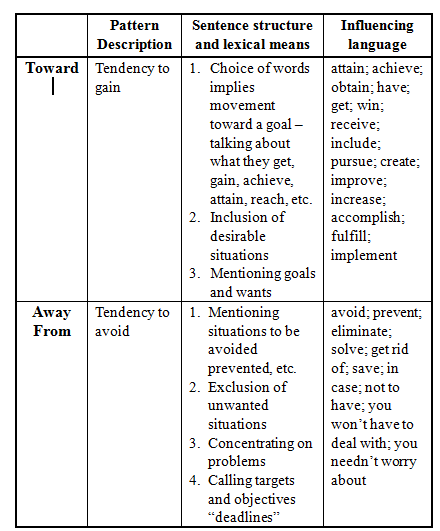

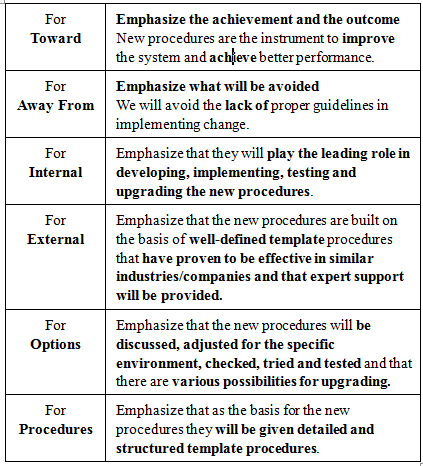

The table below shows how to recognize the motivation direction from what people say, as well as what language to use to meet the identified pattern.

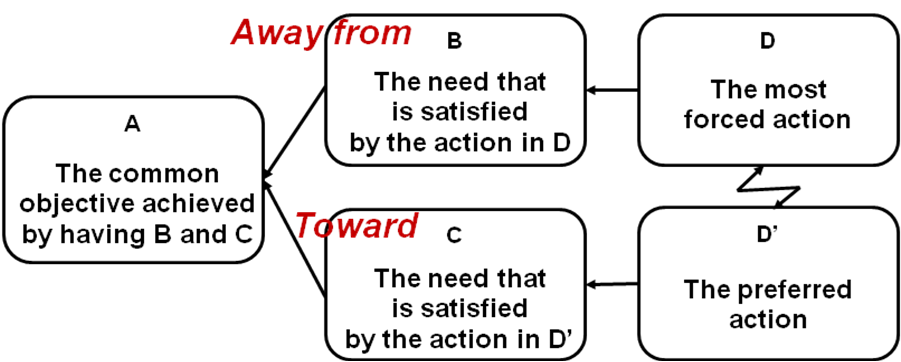

The Toward/Away From approach is useful in understanding individuals’ Dilemma Clouds that present on one side, in D, a forced action, and on the other side, in D’, the preferred action.

Whenever we are faced with a forced action – if we consider taking it, it means that we are trying to avoid some unpleasant consequences resulting from not doing this action. On the other side, our preferred action is desired because through it we are trying to gain something. Therefore, we can conclude that in a Dilemma Cloud the need in B reflects Away From motivation direction. While the need in C, that causes us to want the action in D’, is Toward.

Knowing about the different direction of the needs B and C in the Dilemma Cloud may explain why the beginners often want to have a negative wording of the need in B (“Not …”). They say that they feel that needs B and C are somehow conflicting. It is not a conflict; rather it is just a different direction, Toward versus Away From.

Figure 5: Toward and Away From patterns as reflected in the Dilemma Cloud

Let’s look at a typical example of a Dilemma Cloud.

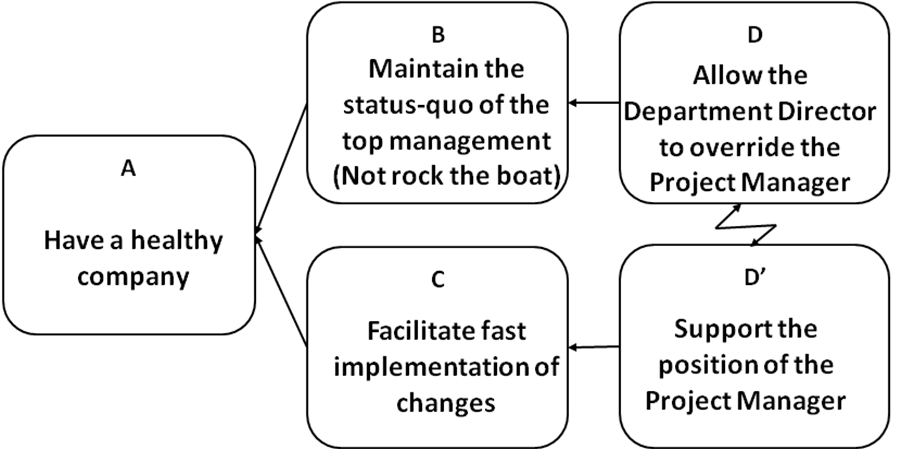

In one of the training sessions in TOC Management Tools, a Managing Director of a project company presented his problem. The company undertook a project for a client. The Project Manager suggested an innovative way to run the project, and was supported by the MD who had been actively bringing new managerial approaches into the company. In the course of the project one of the leading resources disagreed with the PM on some of the activities and wrote an email with her views, copying her Department Director. The Department Director took the resource’s side. The disagreement brought the project to a halt. The MD needed to decide what to do. Below is his cloud.

Figure 6: An example of the Dilemma Cloud

We see that the forced action (D) is ‘Allow the Department Director to override the Project Manager’. The need B that D is meant to satisfy is ‘Maintain the status-quo of the top management’. The MD clarified that he felt he was forced to support the Department Manager who was older, had been working in the company longer than the MD, and had support of some of the top managers. The MD said he could not afford rocking the boat. The need B is clearly Away From. At the same time the MD was putting in a lot of effort to bring improvements into the company. Implementing changes was what he wanted to achieve. The need C is Toward.

What is the practical value of this understanding? Most important, it gives us a deeper insight into what is embedded in the cloud, and what drives the actions. This helps in surfacing assumptions, hence increasing the chance of finding the injection(s) that will break the cloud.

The Toward/Away From concept is also relevant for better understanding of a Negative Branch Reservation (NBR). While our motivation to do an Injection can be either of the Toward position (to achieve something) or the Away From position (to avoid something), the NBR is clearly Away From. We build the NBR to logically prove the likelihood of what we want to avoid, and look for the supporting Injection not to have the possible negative outcome.

Let’s move on to the next pair of patterns.

Internal versus External

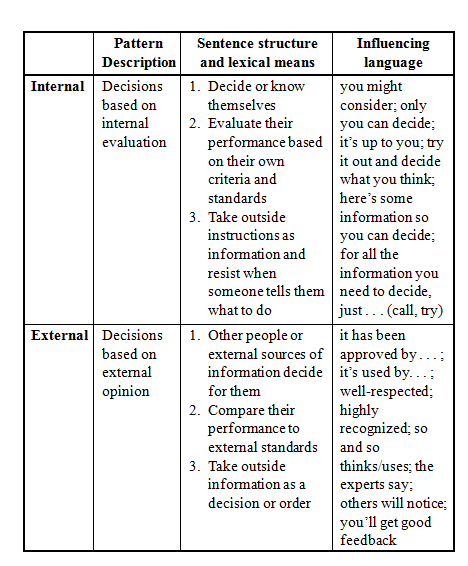

Internal and External is another pair of LAB Profile patterns. They constitute the Source category that distinguishes between the internal and external source of opinion, judgment, and decision making[5].

Internal people act as agents over their environments. They rely on their internal knowledge, skills and actions to produce desired outcomes. They make decisions based on internal evaluations.

External people require outside direction, other people’s opinions, and feedback from external sources. They see themselves as objects, and their behaviour is essentially determined by outside factors.

To help recognize the pattern, the LAB Profile approach suggests asking a person ‘How do you know that you have done a good job at . . . [whatever is relevant for the conversation subject]?’

External people will refer to appraisal from their bosses or clients, or to the targets and measurements they met.

Internal people mostly refer to their own feelings: ‘I know’, ‘I was satisfied’, ‘it felt good’, ‘I liked it’.

It would be reasonable to suggest that in change implementation Internal people present more challenge for the leader. However when, through their internal process of judgment and evaluation, Internals make the conclusion that the proposed change is good, they become its active and sincere supporters. They feel that have true ownership of the new direction.

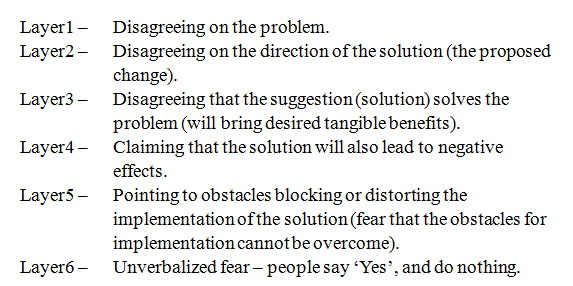

Six layers of TOC to describe resistance or disagreeing on the change[6] are relevant here.

Until we come to Layer 6, people are communicating to us through sharing their concerns, reservations and fears. When we hear their reservations we can “pin” them to a specific layer, and we have TOC tools to deal with them. It is a generally accepted view that if we face Layer 6, when people stop communicating to us, we have missed something in the process of overcoming Layers 1-5.

I suggest looking at the process from the point of view of Internal/External.

I believe that the majority of voiced reservations come from the Internal people. For Internals, what they hear is nothing more than information which they assess, and then draw their own opinion and conclusions. If they disagree or have a reservation, it is natural for them to raise it since they have a tendency to look at themselves as agents influencing their own environment. That’s why they talk to us and share their concerns – with the intention to sort them out. So, we have the “material” to work on.

External people, however, tend to rely on an external source and take the outside information as the instruction or order. With that view, they are more likely not to see much sense in raising their objections, even if they disagree. So, I believe that when we run into Layer 6, in many cases it is not because we have overlooked something in the previous layers. It is that we simply did not have a chance to address these layers, as we may have never been given a signal from an External person that a disagreement existed.

This does not mean that saying ‘Yes’ (or saying nothing) and doing nothing is not experienced with Internal people. When Internals realize that they are not listened to, or their reservations are overruled, they will just decide that they are not interested and withdraw. It is also important to note that when management does not hear ‘No’, the assumption usually is that it means ‘Yes’. Very often, this is not the case. What we see is a person who did not disagree, but is doing nothing of what was expected. Can we really call it Layer 6?

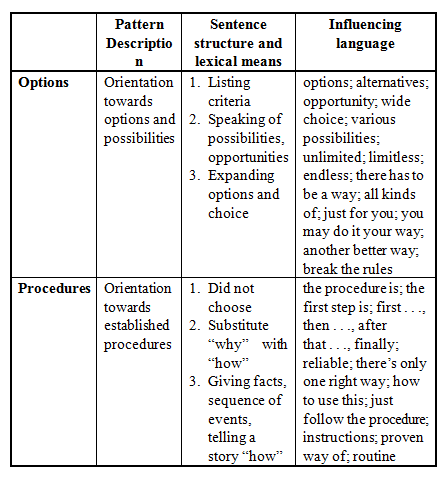

Options versus Procedures

The two patterns in this category, Options and Procedures, reveal the reasoning process model: looking for options or following established procedures.

The question ‘Why did you choose your . . . [job, project, company, etc., whatever is the subject of the conversation]?’ helps determine the pattern.

Options people hear the question WHY and list criteria of their choice or speak about opportunities and possibilities.

Procedures people delete the word WHY and substitute HOW for it, perceiving the question as ‘How did it happen?’ and answerng with a sequence of events.

Options people are good at identifying possibilities and creating opportunities. They are inventive and excited by options, and may become easily bored by the routine. Procedures people like clear sequence and distinct guidelines. It makes sense to have a combination of Options and Procedures people in a team that will be developing new procedures for the change implementation. Options people will be instrumental in exploring various possibilities that the procedures should cover, i.e. specific cases, while Procedures people will look after the proper sequence of the procedural steps and detailed instructions.

Relevance for implementing the TOC change

Let’s see how the knowledge about language and behaviour patterns is relevant for implementing the TOC change.

When people evaluate the proposed change, they express their opinion about it, including their fears, reservations and suggestions. The language that they use reveals their needs and their thinking patterns in the context of the change implementation. If we know how to listen, we will be able to recognize these needs and respond to them, both through our actions and the tailored language of the message.

However, while communicating about the change, we often speak not to one single person but to a group of people. We can expect that different people in the same group will have various patterns for information processing and decision making.

How can we make sure that everyone will hear the message, regardless of the difference in their patterns?

We should combine the words and phrases that will address most of the patterns. With that, people will hear what suits them and filter out what does not.

However, before planning persuasive messages about change implementation, we should be clear on what it is that we need to communicate.

Planning the change

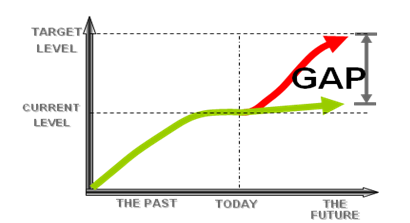

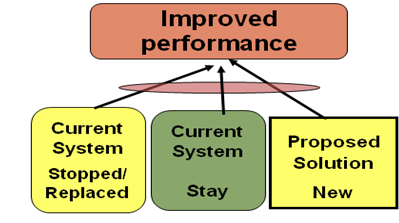

Preparing for the TOC implementation, we proceed from the understanding of the main elements that need to be considered for any system change:

- the notions of the Target performance level and the Gap that prevent us from achieving this target level;

- the three blocks of any system – the parts that should be stopped or replaced, the new parts that should be introduced, and the parts that should stay as they are.

Figure 7: The target level and the Gap

Figure 8: The three blocks of a system

When planning the change, clear communication is required with those involved regarding:

- The target performance we want to achieve, and the benefits everyone will receive as the result of the change;

- The Gap that exists between the current level of performance and the target level;

- Which parts of the system are responsible for the Gap, and thus are “erroneous” and need to be replaced;

- What are the new parts (the solution elements) that must be introduced to replace the erroneous parts to close the Gap, and to reach the target level of performance;

- What are the new procedures to introduce the solution and to ensure daily operation of the injections;

- Understanding that all the other parts of the system stay as they are as we look for the maximum effect with the minimum needed changes.

Guidelines for building persuasive messages

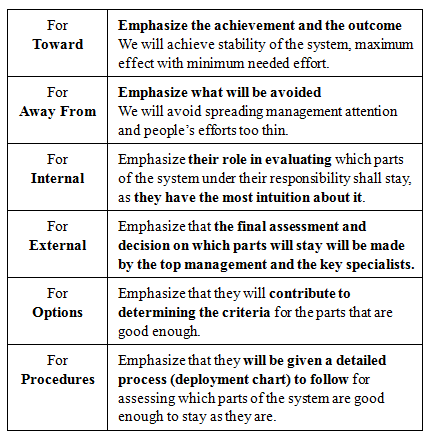

Let’s look at each one of the six messages that we need to communicate about the change from the point of view of the three pairs of communication patterns:

- Motivation direction – Toward/Away From

- Motivation source – Internal/External

- Reasoning process – Options/Procedures

The suggested content and form of the message, even though addressing both patterns of every pair, does not seem repetitive. It is because each time we will be looking at the same issue from two different perspectives. In any case, every person reflects both sides of each pattern category, only to a different extent.

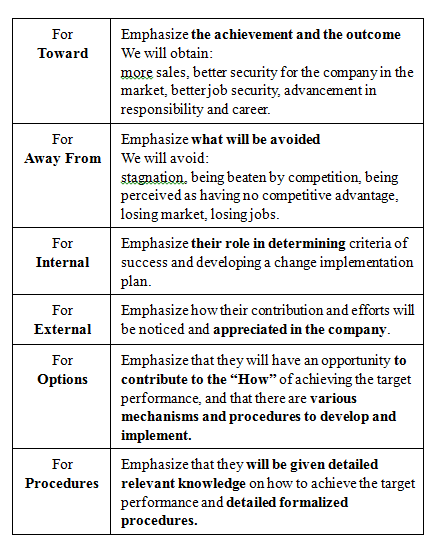

1. How to communicate about the target performance we want to achieve and the benefits everyone will receive as the result of the change:

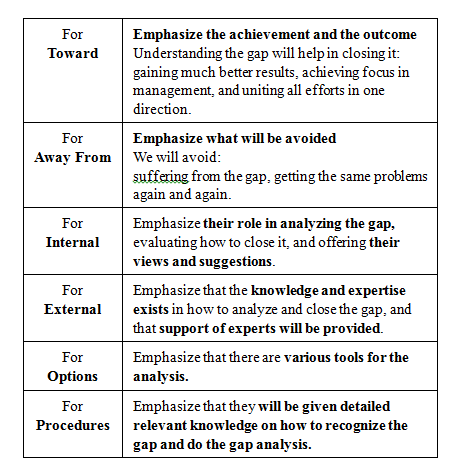

2. How to communicate about the Gap that exists between the current level of performance and the target level:

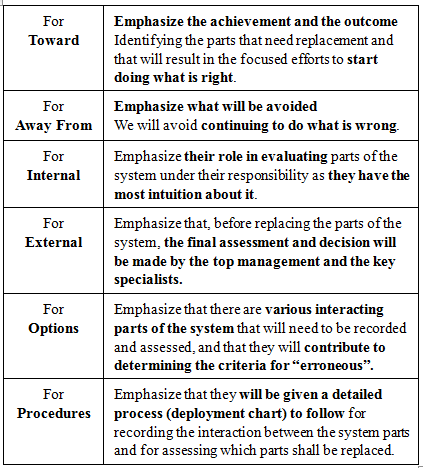

3. How to communicate which parts of the system are responsible for the Gap, and thus are “erroneous” and need to be replaced:

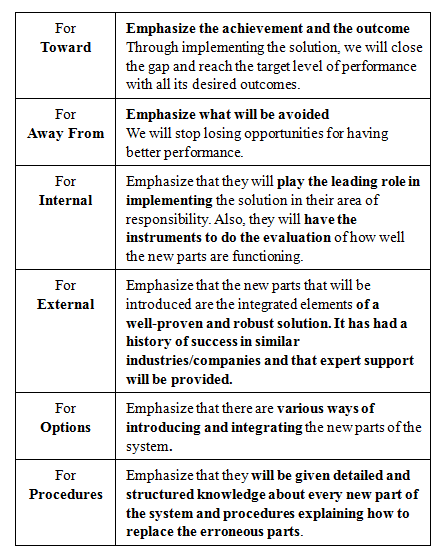

4. How to communicate the new parts (the solution elements) that must be introduced in order to replace the erroneous parts, close the Gap, and reach the target level of performance:

5. How to communicate about the new procedures that will introduce the solution and ensure daily operation of the injections:

6. How to communicate that all the other parts of the system shall stay as they are as we look for the maximum effect with the minimum needed changes:

In the course of a TOC implementation, a TOC leader should also transfer the relevant knowledge about the TOC solution, terminology and tools to the team and resources. There is a need to establish common concepts and common language and ensure that people understand what is meant by the major TOC terms. It will be necessary that they accept and use this terminology on the everyday basis.

Part 2 of the article is presented in Chapter 4.

The continuation of the article looks into:

- Using the communication patterns discussed in Part 1 for communicating the major TOC logical tools: the U-Shape, the Cloud, the Negative Branch Reservation (NBR), the Injection;

- Major stages of the change implementation process

- How to persuade the relevant people to go for change

[1] Rodger Bailey’s LAB Profile examines the particular ways in which individuals act, think and speak and constitutes a classification of language and behaviour patterns grouped in 6 Motivation Traits and 8 Working Traits.

[2] Shelle Rose Charvet, Words That Change Minds, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company, 1997.

[3] Joseph O’Connor and John Seymour, Introducing Neuro-Linguistic Programming: The New Psychology of Personal Excellence, Aquarian Press, 1990

[4] Authors’ remark: The other three categories in Motivation Traits are: Level of activity; Criteria; and Decision factors. The full description of the categories is presented in Charvet’s book Words That Change Minds.

[5] Author’s remark: The meaning of The LAB Profile Internal/External patterns is quite close to that of the internal/external locus of control by Julian Rotter.

[6] Goldratt’s Satellite Program, Session 6 – Sales, 1999

This article was first published in the Goldratt Schools book Leading People Through Change, 2011, published by TOC Strategic Solutions

All materials available on the TOCPA site are the intellectual property of their authors and cannot be reproduced in any other media and used for any purposes without the prior permission in writing of the authors.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!