2. Together: TOC and Lean (Oded Cohen)

Oded Cohen

Oded Cohen is one of the most experienced and well known masters of TOC in the world. He has been developing and implementing TOC since 1978, over 30 years working directly with Dr. Goldratt.

Oded is a Co-Founder and Co-President of TOC Practitioners Alliance TOCPA, International Director of TOC Strategic Solutions, and a co-Founder of TOCICO and was TOCICO first President. Oded is an author of several fundamental books on TOC, as well as many articles and publications.

ABSTRACT

TOC has been around for over thirty years. Thousands of companies around the world have adopted it as their approach and system for managing production and operations. The application of TOC solution for production and operation has been proven to improve their performance to outstanding levels and to provide a solid base from which to support future growth in sales. Due to inadequate access to TOC material in some areas, managers who are relatively new to TOC may find themselves in a debate – shall they go TOC or shall they implement Lean?

In this article, I would like to replace the question of which one is better with two other questions:

1. How do TOC and Lean work together?

2. Which one should managers use first as a platform for converting their production, or operations for service companies, in order to provide outstanding service to their clients?

The objectives of TOC and Lean are identical: to provide a systematic way of managing the flow and continuously improving it. This is based on the confidence that providing the market with a high level of service is a key element in creating a competitive edge for securing the growth of the company.

This article covers the ways TOC and Lean interrelate and, some ideas of how to incorporate TOC in your plants, if Lean is already incorporated into the way you run the production area. If you haven’t decided yet which way to go, I hope my views will help you to make an informed choice.

Introduction

For at least 200 years the world of management and, especially, the management of production and operations has seen many approaches and philosophies. There is an ongoing debate on the subject of TOC versus other management approaches. The perceived merit of making such a comparison is to find which one is better and discover the magic winner that has all the answers to all managerial questions, and will secure everlasting prosperity and success to the companies that employ this winning approach.

The reality is less glamorous. Many of the companies that won awards and recognitions in the early 1980’s for implementing managerial approaches did not show growth in their bottom line and some even went out of business within 10 years of winning the awards. In the late 1980’s, many studies were conducted to distinguish TOC from TQM –Total Quality Management. Dr. Eli Goldratt then wrote an essay[1], challenging the concept of the “or” and suggesting the direction of the “and”. When the different managerial approaches have the same goal, why not adopt the mindset of amalgamation. Create a united approach that complements each other, while taking the strong points from every approach and covering the weak points. Many organizations adopted this attitude and incorporated TOC into their TQM approaches.

In the spirit of the “together” I was involved in writing “Deming & Goldratt”[2] with Dr. Domenico Lepore. Together, we built a ten step approach we called the Decalogue that combined concepts and practicalities from Deming’s TPK, the Theory of profound knowledge, and Goldratt’s TOC. This book has provided a bridge for the Deming community and the TOC community to know about each other, and to enhance their own approaches by introducing ideas, concepts, methodologies and procedures from the other approach.

In a similar way, I would like to offer my support and views to bridge between the Lean community and TOC by using my deep understanding and knowledge of TOC concepts and of the TOC solutions.

For over ten years, we have been witnessing the continuous debate of TOC versus Six Sigma and/or TOC versus Lean manufacturing. Many companies, with the help of practitioners from both “camps” have succeeded in creating an amalgamated approach that has successfully worked for them. If you want to substantiate the above statement, you need only to search the web for TOC and Lean. In a recent search with Google, I found over 300,000 references. Many of them even use the name of the combined approach, TLS; TOC-Lean-Six sigma. These references describe not only how to combine these approaches but also, and most importantly, the value and the benefits of the combination.

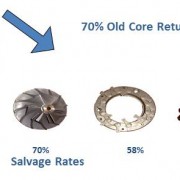

One early example of TOC and Lean, released to the public domain, is the US Marine Corps maintenance depot[3] that can be found on TOC.tv. They presented outstanding improvements in reliability, level of output, reduction in lead times, and cost. In their case, TOC was the lead approach.

In this article, I am using my own experience in working together with the Lean team in a British company, two years after they successfully implemented Lean in their company. Like the Marine Corps, this company refurbished armed vehicles. The improvements in the first two years were remarkable, yet they felt they were stagnating and could not squeeze out more improvements. The plant manager read The Goal and asked us to visit them. Immediately thereafter, we started working together to incorporate TOC into their environment.

Both TOC and Lean promote continuous improvement.

TOC clearly states that the role of management is to ever improve the performance of the area under their responsibility. The performance of the production area is determined by the flow. Hence, the most important role of production management is to maintain the flow and to continuously improve it.

In his article “Standing on the shoulders of giants”[4] Dr. Eli Goldratt outlines four major concepts for managing flow:

- Improving flow (or equivalently lead time) is a primary objective of operations.

- This primary objective should be translated into a practical mechanism that guides the operation when not to produce (prevents overproduction).

- Local efficiencies must be abolished.

- A focusing process to balance flow must be in place.

We shall use these concepts for examining TOC and Lean and getting the most of both. For that we need to cover three areas:

- The alignment between both approaches

- The areas where TOC agrees with Lean

- The areas where TOC ideas differ from Lean

Thereafter, we can discuss the practical ways of how to work TOC & Lean or Lean & TOC. Please note that I am referring in this article to production management. Yet, everything that I say here is relevant for managing any flow environment. The more general term for managing any flow is Operations management.

Concept no. 1 – Improving flow (or equivalently lead time) is a primary objective of operations

The alignment between TOC and Lean

There is a full alignment between the TOC and Lean on the first concept – improving the flow is the primary objective of production management. Production is the function that is responsible to convert, through flow, raw material and components into a sellable product. To ensure the contribution to the overall performance of the company, production has to complete every work order on time, according to the specifications (quality), and within the agreed cost.

The production lead time is a critical factor in generating value, as money is generated for the company only when its product has been delivered and the customer pays for it.

Production flow is comprised of several dependent activities. Lean suggests mapping the key elements of the lead time though the recording of the Value Stream (VS). The value stream determines the overall lead time of production. By mapping the value stream, management signals that the flow is of utmost importance. The VS diagram is posted in key areas in the shop floor, and everybody is aware of the flow and their own role in the value stream. The VS is in line with step 2 of the Decalogue; seeing the system. To improve a system, we must know the system and see it as such; where it starts and how the major components are connected.

Value Stream is a solution promoted by Lean. It is a powerful solution. So, what is the problem with it?

The problem is the disconnection between planning, execution and improvement. For production planning and control, a fixed, predetermined time is used. Usually it is called production lead time (PLT). Production starts at a given time and is expected to be completed within the agreed time. However, due to disturbances, disruptions, and statistical fluctuations of the processes, many times the order is not completed and shipped on time. Traditionally, the solution for this problem was to increase the production lead time and start the flow even earlier. This solution only made the situation worse. The earlier that work orders are released to the shop floor, the more orders we have there. This creates even more traffic congestions as the load on capacity constraint machines grows and the queue gets longer and longer. Increasing the production lead time may be a short term recovery action, but it cannot be a regular solution as it conflicts with the first concept of the flow that seeks to improve the lead time.

The VS was introduced to facilitate systematic improvement. It helps to focus management and people on the flow by providing a flow map of the products throughout the shop floor. It provides the platform for continuous improvement where other Lean tools and techniques may be employed. The activities of the VS are grouped to be performed in work centers. The Grouping is done in such a way that the timings to perform the grouped activities are of a similar length. Usually, the grouped activities are performed in one work station. The time to perform grouped activities is called Takt time. The overall expected production lead time is calculated by multiplying the Takt time by the number of grouped activities. The calculated production lead time is used for planning purposes, and for promising delivery times to the clients.

Likewise, TOC acknowledges the critical role of production lead time for flow management: planning, controlling the execution, and for continuous improvement. However, TOC suggests a shortcut to get the system going and achieve immediate improvements in performance. This is done through the establishment of the Production Buffer (PB). PB is the total elapse time that is allocated for the production to complete the order. The term “buffer” is used by TOC to denote time including more than the average processing time on the machines (touch time). It also includes allowance for setting-up the machines for specific parts or products, queue time in front of occupied machines, wait time for missing parts in assembly, as well as unexpected problems known as “Murphy”. In most production environments, the touch time is a small fraction of the production lead time (1% or less).[5]

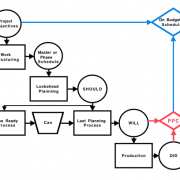

The SDBR (Simplified Drum-Buffer-Rope) is the TOC solution for MTO – Make to Order. MTO is a production environment that produces to customers’ orders. SDBR uses the production buffer (PB) for flow management. When the actual touch time is so small compared to the elapse time, there is no need for a detailed mapping of the value stream. Actually, for SDBR, we propose choosing an ambitious size for the PB which is challenging but achievable; shorter than the production lead time that was used by production at the outset of the TOC implementation.

Managing through the TOC production buffer provides the same managerial focus as the value stream. The advantage in using TOC is the ease and speed of implementing the solution, as well as integrating it in to the computerized systems. Sometimes management can use simple excel files for the purpose of flow management.

Another difference with TOC is the upfront and open commitment to the first concept – improving the flow. For the successful implementation of the TOC solution, management has to commit to adopting the mindset that flow is number one priority. This is reflected though making on-time delivery of customer orders the prime measurement for production performance. Thereafter, in a systematic way, the production buffers are adjusted to improve the lead time, and for the company to gain competitiveness in the market place. The concept of production buffer is captured also in the name of the TOC solution SDBR. The B stands for Buffer.

The major difference between TOC and Lean in maintaining and controlling the flow is with the mechanics that are used. Lean uses the value stream. Given that there is no economical justification for building dedicated production lines which are effective but relevant only for very high volume repetitive products (such as cars, electronic equipment etc.) Lean tries to emulate lines through the concept of Takt. Takt is the mechanism that provides the rhythm to the value stream. Stations are organized in such a way that they have roughly the same process time. Thereafter, every Takt time, the Work Order (WO) moves from one station to the next one. As such, the flow is established and work stations have to keep up with the pace.

For example – the MRO company that I mentioned above had 10 work stations covering the entire value stream, with a Takt time of 2.5 days (two moves per week). That determined the total lead time of 50 days. This was a significant reduction from the 70 days that they started with. Stability had been improved and more vehicles were shipped on time.

However, there are several disadvantages to the Takt approach:

- It is not always easy to group the activities in one work station that will fit the Takt time.

- To compensate for fluctuations in performance, some slack time is built into the Takt time. Potential gains due to positive variation when a station completes its activities earlier than predicted are not past to the flow and are wasted in waiting.

- The Takt time should be equal for all products that are produced in the “line”. This reduces the flexibility and ability to run different products and product families using the same resources.

The TOC solution covers for these disadvantages. Once the WO is released for production it can move freely between the different work stations. Once work on the WO is finished on this station, the WO moves to the next station. The loading to the machines is done according to the priority determined by buffer management ensuring that higher priority is given to WOs that are close to their delivery dates. The TOC solution accommodates products and product families with different Production Lead times. Also, it can accommodate orders with short response time (for premium prices).

Concept no. 2 – Prevent overproduction

This primary objective should be translated into a practical mechanism that guides the operation when not to produce, thus preventing overproduction.

In the second concept there is also a full alignment between TOC and Lean while the mechanics differ.

Lean prevents overproduction by using two major methods:

- Controlling WIP and the start of new production WO, by the number of empty slots available. The number of holding positions, when a WO is parked and not worked on, is limited. Ideally, work on a new WO should start on the first station only after a WO has been completed and has departed from the last work station of the VS. It is the concept of one-out one-in. The number of WOs in the VS is fixed. After one WO departs from the VS, a new one enters.

- In points of assembly – using the 2 bin approach for the parts and components that are supplied from a feeder. The parts are stored in 2 bins available for assembly to use. Once one bin gets empty, a signal is given to the feeder to produce and deliver a replacement bin.

Both mechanisms prevent overproduction. They present the concept of fixed WIP. The first one fixes the number of WOs in WIP to be the number of work stations in the VS. The 2 bin mechanism limits the WIP to 2 bins only. As long as people adhere to the instructions, it is impossible to release more materials to the shop floor.

The mechanism of one-out one-in for the VS was significant in the MRO environment. Before the Lean implementation, the tendency was to disassemble the vehicles as soon as they appeared at the depot. This elongated the time that the vehicles spent in the depot while the army units were missing them. They wanted the decommission time to be as small as possible.

The VS prevents overproduction and provides stability. Thereby, it helps to improve the overall performance of the production area.

At the same time it is important to know its shortfalls:

- VS is applicable in a highly repetitive environment that has stability in demand for long periods (years).

- VS is applicable for products and product families that have the same structure and about the same production times.

- It is not planned to provide “fast track” service to some of the orders. All the WOs have to follow the same flow in the sequence they have entered into the VS.

- The VS does not address the issue of the feeders that are supposed to provide parts and subassemblies to the work stations of the VS.

The availability of parts and components for assembly in the MRO company that was mentioned above was the major reason that TOC was called in. It was impossible and impractical to create a value stream for all of the feeders. The VS suffered also from shortage of non-standard parts. In such cases, some of the vehicles finished their VS journey incomplete and were put in holding positions until the missing parts arrived. In some cases, vehicles were removed from the VS in order not to block the other vehicles that could move.

In summary, shortages of parts for the VS caused disruption to the flow and hurt on-time delivery to the customers.

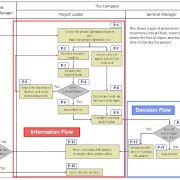

SDBR has a simple mechanism to prevent over-production without having the shortfalls of the VS. It is called the “Rope”, meaning choking the release. WOs are not released to production before their calculated release date. This date is calculated as the promised shipping date minus the production buffer time. The rope reduces the amount of open orders. This reduces the overall load on the machines and resources. The open orders get the right priority and, due to better availability of machines, are completed on time. That is the reason why correct SDBR implementations bring significant improvement to production through increased Due Date Performance (DDP) and reduced WIP within a short time.

The Rope mechanism is used not only for the main stream but also is extended to the feeders. Once the delivery date is committed to the customer, the same production buffer is used to signal the feeders to start their activities to ensure that the parts will be available for assembly.

The above two mechanisms of the SDBR, buffer and the rope, provide a simple and practical solution to prevent overproduction without risking the delivery dates. The simplicity of the system is denoted also by the name SDBR – the “S” stands for Simplified Drum-Buffer-Rope.

Concept no. 3 – Local efficiencies must be abolished

This is an interesting point.

Conceptually, TOC and Lean should be completely aligned.

Efficiencies as performance measurements and, the use of cost based management accounting for decision making, should be stopped. The major problem with this type of decision making is that it contains a real risk that local decisions will be made that will have negative impact of the flow. The late Dr. Ohno of Toyota admitted that he was forced to fight cost accountants, and to chase them out of the factories in order to allow his system to work. By the way, the TPS, Toyota production system, is not pure Lean. In fact, the Toyota people in Japan do not agree with the term Lean to describe their system.

In reality, the descriptions of Lean cover a lot of techniques and methodologies. They do not contain any message regarding local efficiencies. This presents a risk to the Lean implementation. Local management may understand that to allow Lean to work they should stop local efficiencies. That can bring them into a clash with their corporate headquarters, if they are a part of a larger group. On the other hand if the local management decides to abolish local efficiencies, and does not know with what to replace them, they may lose control as the managers reporting to them will not know how to make the right decisions.

Abolishing local efficiencies was high on the TOC agenda from as early as 1980’s. Besides the demand to stop using local efficiencies for measuring performance of departments, machines or manpower (“what to change?”), TOC has also provided clear, practical concepts and methods to replace them (“what to change to?”). Such as:

1. Making on-time delivery the prime measurement for production performance:

- DDP – Due Date Performance – to denote the level of reliability of the shipping according to the promises to the customers. This is presented through the percentage of orders that are shipped on time (on the actual date that it was promised or before, but no later than the promised date).

- TDD (Throughput Dollar Days) or TVD (Throughput Value Days in local currency) to denote the financial impact of the customers’ orders that are late, and the amount of days that they are late. This has a financial impact on the company as it hurts cash flow. This is the amount of money that could have been already in the company’s bank account multiplied by the number of days (that the money could have generated value for the company).

2. TOC (Throughput) Accounting – providing management with a set of operational measurements to bridge between the local decisions and actions to the global performance. The three operational measurements are:

- Throughput (T) – the money generated by the system.

- Investment (I) – the money invested in the system, including facilities, machinery and materials, and

- Operating Expenses (OE) – all the money that is regularly spent on running the company and generating Throughput.

TOC emphasizes that production management should focus on flow. If flow is number one, then all the rest, quality and cost, will fall into place and will be in control. In the SDBR Solution, “D” stands for Drum. This is the concept that customers’ orders drive the production system. The company’s commitment is the driver for the production system. The shipping plan (schedule) is the way the company builds market awareness and its acceptance as a reliable supplier.

There is no conflict between TOC and Lean on the third concept. It is just that it is not a part of Lean. We believe it is absolutely necessary for a company to establish its position in the market place. TOC can cover for this void.

Concept no. 4 – A focusing process to balance flow must be in place

This is the area where TOC and Lean are not only aligned but also can work together in full synchronization.

To balance the flow, there is a need to address and remove any obstacle and obstruction to the flow. Once we do so, we allow production to flow better, and faster. This is where all the tools and techniques of Lean can be utilized. Disruption to the flow can happen due to lost capacity from machine breakdowns, quality problems, process instability, long set-ups, etc. There are very powerful tools and ways in Lean to address such issues.

TOC is a managerial approach. It deals with managing the flow. TOC can help in highlighting the problematic areas in the flow that must be improved. But, TOC does not have any technical improvement techniques. TOC completely relies on Lean to provide improvements in the places where these improvements will contribute the most to the objective of improving the flow.

Whereas the TOC implementations incorporate Lean in the POOGI – process of on-going improvement, we have concerns about applying the Lean improvement in isolation from the global view of the flow. The fact that Lean does not call to abolish local efficiencies, gives rise to the TOC concern. If local efficiencies are not abolished, then the prevailing decisions made by management are cost-based. That can lead to waste of the efforts that are put on improvements. For example: Setup reduction is a very powerful technique. It can help dramatically to improve the flow. If we have a machine that is lacking capacity, setup reduction will create additional capacity that can improve the flow. However, if a non-constraint machine, a machine from which the load demanded is less than 70% has a high setup time, a reduction in the setup time will not necessarily translate into a better flow or more throughputs. As the operator of the machine is on salary, the company is not going to realize any major benefit from the effort to reduce the setup.

TOC provides direction for management focus, as they know which resources are constraints and which are not. As the improvements are focused on improving the flow, the first priority should be assigned to deal with the CCRs, the resources that do not have the capacity to maintain the flow. The second priority should be assigned to the non-constraint resources that disrupt the constraints or cause major delays to the flow.

TOC has a strong focusing mechanism for POOGI. It is called Buffer Management. It is a part of the SDBR solution. While a work order is in progress its status is constantly monitored based on the consumption of time by this WO from its production buffer. At certain points in time (determined by the on-going managerial procedures of running under the SDBR solution), the system prompts sampling of the flow. While sampling, the system checks for the reasons for the delay. What is the WO waiting for? It may be waiting for a resource that is busy, for materials that were late to arrive, for documentation or drawings from engineering etc. The date is recorded and analyzed. Periodic meetings, ideally weekly, review the findings and decide on improvement initiatives to address the reasons for frequent and repeated disruptions to the flow.

The improvement initiatives employ Lean techniques, but not only Lean. Some of the causes for disruptions to the flow may be connected to the human factor such as: lack of skills, knowledge, awareness, attitudes, authority etc. The analysis of the causes can be done by using TOC tools and Thinking Processes to deal with such problems. From time to time, a deeper analysis may demand the development of a more strategic solution using the TOC methodology for developing a solution.

We believe that TOC buffer management is a good focusing mechanism for all the improvement initiatives of the production area. Every problem solved and every disruption removed improves the flow, makes the production area more reliable, and provides a potential competitive edge for the company.

Conclusion

TOC and Lean work together!

The TOC community works together with Lean leaders and practitioners within companies that are using Lean. Such collaboration is a win for everybody.

If you haven’t implemented Lean yet, then my recommendation is for you to list your expectation from taking the initiative, TOC or Lean. Determine the criteria and check the suggested alternatives against these criteria. And then, make the decision according to what is more beneficial and preferable for your company.

[1] E M Goldratt – TOC Journals Volume 1 no 6

[2] Deming and Goldratt, Domenico Lepore and Oded Cohen, North River Press, 1999

[3] U.S. Marine Corp – Logistics Base – presentation – TOC.tv

[4] E M Goldratt, “Standing on the shoulders of giants” – published also in this volume

[5] Please note that environments with high touch time of over 10% of the current lead time need a special application of the TOC solution for production.

This article was first published in the Goldratt Schools book TOC for Production Management, 2010, published by TOC Strategic Solutions

All materials available on the TOCPA site are the intellectual property of their authors and cannot be reproduced in any other media and used for any purposes without the prior permission in writing of the authors.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!